The future foreseen

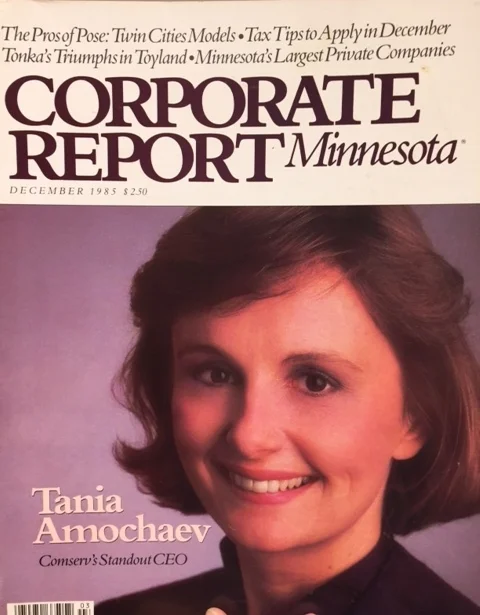

Looking for old family photographs, I find a package of mementos of my own business career, saved by my mother. My young face is on magazine covers, business advice columns in the Minneapolis paper, in a Forbes magazine.

An old newspaper quotes 'the only woman keynote speaker' at a conference I do not remember attending as saying "she expected people would find in a few short years it was more economic to read the newspapers off screens rather than printed on paper."

It takes some research to figure out that the newspaper and conference are both in Australia. The date is just weeks after my wedding in September of 1982. Some 35 years ago "Ms Amochaev spoke of merging technologies which would result in screen-based telephones with special interfaces to access databases, such as telephone directories, and do home banking, teleshopping and other transaction processing. Telephones and computer terminals would become the same tool."

I remember that we had to postpone our honeymoon, and that our first year of marriage resulted in about three months together because we both traveled so much for our jobs. I do not remember speaking at this conference, and certainly not this very prescient forecast of my favorite device, the iPhone. But sometimes life is stranger than fiction.

I found every letter I wrote to my parents as a young woman living in France, every postcard sent from travels around the world. My life is laid out in detailed notes written in Cyrillic Serbian—a language I would have denied ever writing in had the visible proof not been sitting before me.

I also found a letter sent by my parents to the Russian scout camp at Bucks Lake. My mother is sad to tell me there are no airplanes to Quincy, California, so she has sent the mysterious black felt I requested by surface mail. My father complains that we don't write— Camp is two weeks long after all—and insists we send a note to my cousin Helen at 333 18th Avenue—an address burned into my brain from childhood. I idly wonder if my cousin, when going through her mother's things in that same apartment 50 years later found a letter from me dated August 1962, surely some years before she herself could read.

Introducing Tania Romanov

The birthing process for a human child takes about nine months. An elephant gestates for almost 2 years, the longest in the animal kingdom. Trying to find an appropriate metaphor, I move on to the inanimate. 'The biggest, baddest equipment' list includes a 31,000,000 pound bucket-wheel excavator, selling for $11 million. This device moves enough dirt daily to fill 100 Olympic size swimming pools, but can be built in three years or less. In China, a new city can be populated in that time.

And all I am trying to deliver is a book that in printed form will probably weigh less than a pound and in digital will fly through the air and land on your device adding no weight at all.

Its sweep—three generations of women facing exile and displacement in the Balkans over the last hundred years—is not trivial. But still. The original incubation for this book was a mere month. That's how long it took me to complete the first version.

The resulting Word document was so huge and unwieldy it took me a year to learn how to do the first rewrite. How do you comprehensively edit something that takes 12 hours to just skim quickly? And how do you backtrack when you're heading the wrong way through a maze of partially completed re-edits? And how do you learn which well-meant feedback to incorporate and which to ignore?

All this is a preface for the news that my book is nearing completion . . . Or at least completing its sixth or seventh or eighth rewrite . . .

Now, I am thinking about publishing more seriously. I have two publishers interested in working with me. They are very small publishing houses and I am trying to sort out the difference between working with one of them and self-publishing.

Having spent the last few years learning how to write, I am trying hard not to get sucked into spending the next three years learning about the incredibly explosive changes in the world of publishing. A fascinating subject in its own right.

But this week, that study led to a very important step in my process.

I learned that presentation is incredibly important. That the cover design of your book is absolutely key. The inside layout, the number of pages, the quality of the paper. Everything matters.

Imagine my dismay upon learning that the author's name itself is just as crucial. "If your name is hard to pronounce or spell, you will drag down your readership . . . It just might be the final nail in the coffin for your work." Lacking a good name, the author is encouraged to just find a better one.

And I of course have lived all these many years with Amochaev.

I call my friend Judy to commiserate. "It's not fair that you have this great name of Hamilton." I say.

"Uh, oh. I do understand." she replies. "It took me four years to learn how to pronounce your name, Tania." I think she was trying to be helpful. "Why don't you try your married name, Hahn?"

"Well there are many ways to misspell that . . . Han, Haun, Hawn . . . "

"Besides," I continue. "It's not particularly relevant to my writings about Russia and the Balkans."

"What about your mother's maiden name?" She asked.

"Marinovič?" I say, hesitantly.

"That's worse," she says. "What about her mother? Your grandmother?"

"I can just imagine what you're going to say about that." I say. "It's Rojnič."

"Oh . . ."

"Oh my God!" I say "I've got it!"

And so I do. I have it. I have my perfect name.

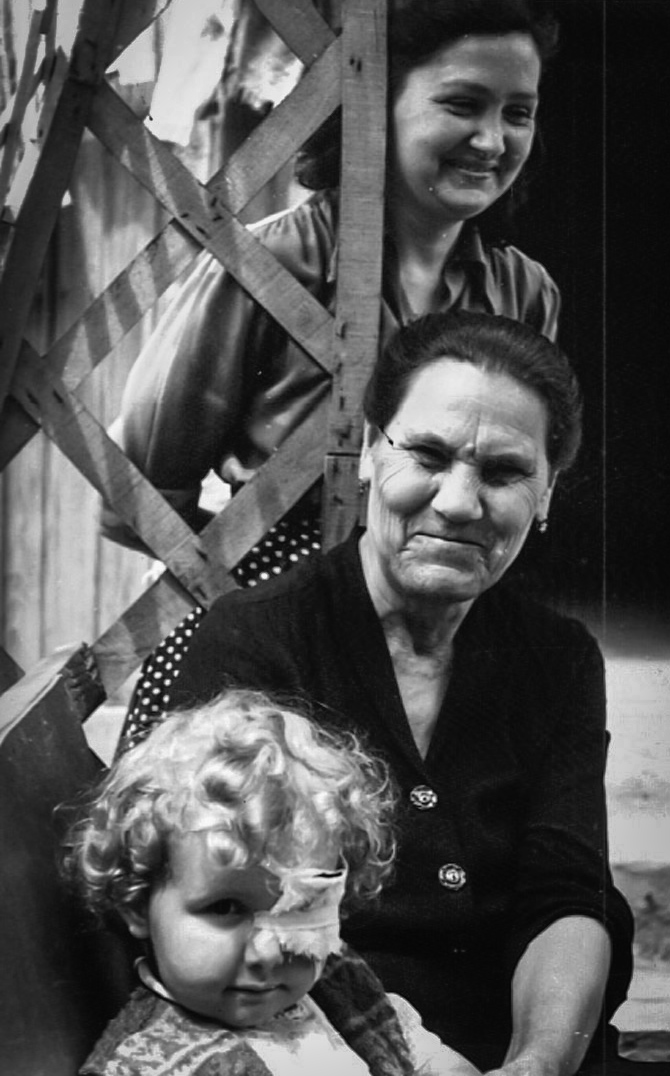

I remembered my next book, the one about my father. It starts out with my grandmother cursing her own mother-in-jaw. My grandmother. A grandmother whose memory I mostly reviled until that very moment.

Daria Romanov.

Romanov.

ROMANOV!

It just so happens that my grandmother shared her family name with the ruling dynasty of Russia from 1613 until 1917. The dynasty that her family fought to protect until the day they had to flee their country shortly after the murder of the last Romanov tsar. A dynasty even the new tsar, Putin, is apparently considering resurrecting.

And so a new author was born. After a gestation period of many years—or just moments.

Tania Romanov.

Walking my way

Walking my way

You grow up bemoaning your foreignness. The parents and relatives speaking broken English with awful accents. The funny clothes your mother sews for you on her Singer. A brother called Sasha sent to school in short pants on his first day. The derogatory "off the boat" references. The taint of being from the land of the "dirty Soviet Commies." Having to go to Russian school. Being born in Yugoslavia, your mother speaking Serbo-Croatian to you, a place and language no one else has ever heard of. The math professors working as janitors. Christmas showing up on January 7...

And then slowly it becomes "in" to have a heritage. You learn other languages easily. Your husband revels in the stories he hears at tables full of foreign dishes, sitting with old refugees sharing great stories.

Meanwhile, both your homelands disintegrate in radically different ways. Who are you when your country of birth changes every time you renew your passport?

And now you sit at a table in Slovenia, in the ex-Yugoslavia, a few miles from Italy and the refugee camp where you spent your early childhood, basking in a glow that reaches deep into your soul. Hands reach in a toast proposed and echoed by voices known from birth, others gained through your life history, some as recently added to your life as a week ago. But all closer in spirit and full of more warmth than you ever imagined life could contain.

The waiter, embarrassed by his bad English, hears your accent and suddenly he's your friend and you learn he's Serbian, with a Moldavian/Russian wife called Tania. Of course.

Thank you, Zora and Tolya, for a heritage so complex and rich that tears roll as I remember you. A toast to you, my parents who walk with us.

"На здоровье!" "Živjeli!

Samburu Softening

Samburu softening

I sit deep in a Samburu hut which is built of twigs, old cloth, ripped cardboard and random debris because the current lack of local grazing area has pushed the cattle too far away for dung to be feasible as covering. The head of the family sits watching me. His face closed, he observes without any affect or emotion.

From the outside, the four foot tall structure looks tiny, but inside there are three areas, and a cook fire in the far end of the entry. The couple and babies sleep in one cattle-hide lined compartment, young people in the other. The men rest their heads on triangular pieces of wood, but a woman my age confesses to the pillow I spy in a corner.

The women have built the home, clean the area, tend the goats, cook the food, bear and care for the children. The men sit in deep, serious discussion, debating matters of state. Yet they are the rulers of the roost.

Light from the entry turns the regal face before me a beautiful tone of deepest bronze, and lights it so I can use my phone. I show him his portrait and feel a slight thaw. Then I flip the camera to selfie mode and place it in his hand. He stares at it, shifts it about and finally sees his own face staring back. I gently reach for a finger on his other hand and feel the muscles release. Together, we push the large white button, but our jerky motion moves the focus. I try again, then push the playback button. His face eases a bit more as he looks at his image.

Soon he has the concept, and is satisfied with the results. He grins hugely when reviewing, but prefers a serious self image. A baby wanders in and is soon part of his scene, followed by a young child. Now the doorway is blocked by observers, but it's hard to explain why it is now so dark he cannot shoot, and the crowd is too thick to clear.

The chief stands up and walks off with my phone, bestowing a view of the image on his court. He is beaming when he returns the device, and holds my hand for a long moment as I say "Lesere," in farewell.

"Ashoalei," he says, the word I have just learned means thank you in Samburu.

Tania

Himba and Herero

Two groups populate the remote northwest part of Namibia near the village of Purro, and trite expressions like "chalk and cheese" come to mind in describing the Himba and Herero. They share dark black skin and an apparent common ancestry, and the two groups peacefully coexist in this barren desert land. But it would be hard to mistake one for the other.

The Himba live in tiny rounded huts built of twigs and covered with cow dung and random bits of cloth. The Herero favor tiny rectangular houses much smaller than a typical trailer—also made of dried cow dung. The Herero, however, have found a Christian God and a church sits squarely amid their structures.

It is their dress that leaves you breathless in its diversity, although both groups are incredibly classy in their garb.

The Himba wander nearly naked, breasts glowing and legs bare. Their butts are covered with wonderful brown furry strips of domesticated stock—primarily cow or the quirky looking goat-sheep. Their legs and arms are covered in metal bracelets and their necks wrapped in layers of necklaces made from bits of polished ostrich eggs and porcupine quills. Everything—skin, hair, and leather covering—is deeply soaked in a red powdery layer made by scraping a stone the color of dried blood—called an okla—on rough rock. This lends them an otherworldly glow as well as protection against sun, insects, and body odors.

The Herero, taught by the nineteenth century missionaries to forsake their lewd nakedness, wander this same barren desert land dressed as if Alice in Wonderland grew up into a perpetual tea party with the mad hatter. Ruffled voluminous skirts cover bellies whose ideal form, I was told, is the hippo, preferably well rounded to demonstrate wealth. Jewelry is minimal, but head-dress seems mandatory. Imagine a visit to Ascot in high season, preparation transposed to a remote desert milliner's. The frame that forms the shape to meet a lady's fancy is a coat hanger lifted from milady's dresser, and instead of birds perched on blond locks you get a form of cattle horns perched over glowing black cheeks. Colors are bold, patterns vibrant, and designs seem unchanged from the days when the Christians arrived and the Victorian style still flourished.

Yes, there are seasons in California...

Twice a year the sun sets precisely behind the southern tower of the Golden gate Bridge. It's working its way north in the spring, heading towards Mount Tamalpais. This year I was enjoying my usual sunset Aperol, watching the light get interesting, when it hit me that this was going to be the moment. I grabbed my phone, ran outside, and snapped. I know it's just a memory shot, but what a lovely memory.

The timing coincided with the blooming of the dogwood and rhododendron forest up in Healdsburg. Where the steps lead through the dogwood trees we once parked cars on an ugly driveway. When I look at it all through the living room windows I am standing in what was once the garage. Now the cars park outside out of sight and I bask in the beauty.

Almost 30 years ago our friend Mary Lou came to visit from Paris. We had brought some small neglected "as-is" rhododendron from a nursery to plant in the redwood forest. I can still see her taking turns swinging the pick-ax at the rock hard Sonoma clay. It took three days and gentle soaking overnight to dig ten holes deep enough to shelter the roots. We had read that fir needles form the kind of acid-base those plants love, so the giant holes were then filled with that same clay mixed with needles and duff. We lovingly spread the roots, making sure they had room to breathe and spread. Those ugly ducklings are now 20 feet tall and happy as pigs in, well, you know.

In those early days on this property, we also brought home a much larger clematis to cover the wall of the toolshed. Harold felt we didn't have the time to wait for it to grow. We had prepared the space and finished the planting before lunch.

Unbeknownst to us, while we enjoyed lunch down by the pool, the deer enjoyed lunch out by the toolshed. Until that day we thought it was cute that generations of deer roamed freely by the house. Returning from lunch to stare at the empty space rid us of that romantic notion.

The deer fence now keeps the deer and the far more destructive wild boar out, but the clematis still struggles on that wall.

Taking New York

A Chinese violinist, a blues trumpeter, and the Central Park Zoo's musical animal clock competed for my aural attention. Tulips and blossoming trees fought over my eyes. Kids ran around and cried out while adults try to herd them into lines to wait for tickets. Joy was out in force in the sunlit park.

Runners, bikers, walkers, sitters. French, Spanish, Russian, polyglot, even American. Most, like me, had their smart phones out. Someday, when this era is history, when we take pictures by blinking and communicate with electronically focused thought waves, that will be an interesting fact.

Along a nearby street, firemen were exiting a tower. I asked for a photo. They were excited, kept fighting over who would take the picture and who would be in it. As I walked off I wished them a good day, hopefully with no fires.

"But that's the fun part of this job," one of them said. "As long as there aren't any people involved." Of course. Firefighters need fires just like news reporters need news.

On 56th Street, I asked a couple of TV reporters what they were following. "Donald Trump, of course." We were in front of Trump Tower. I kept thinking about the news of the blonde-haired phenomenon who had just won the state primary. Sad to say, what once felt like a horror flick now feels like a reality show. I find myself growing inured. There's an inevitability about it that numbs the mind. I can't get over the fact that it's the blue-collar white working man who is so enamored of the rich kid who inherited his wealth.

"It's beyond my skills of articulation. My mind gets fuddled on the way to an explanation."

Those might be the opening lines of an eventual rap musical called Trump. Last night at Hamilton, I toyed with the ironies between the words on stage and the realities of Trump. Hamilton took the Pulitzer this week. Trump took New York. For a $1000 contribution I could've had my picture taken with the star of the former. I can't even guess the price of the latter.

For now, this is Tania, signing off with all the important news from New York City.

The Magic of Mushrooms

It's been a very challenging mushroom year. In spite of all the rain, we have found very few edible mushrooms. Because of all the rain, we have spent hours tromping through the woods.

After almost 30 years of mushrooming, my obsessive care in picking only a few well known varieties always disappoints new pickers who dash from specimen to specimen.

"Oh look at this mushroom! What is it?"

"Oh… Just a brown mushroom."

The same conversation might be had about a white mushroom, a pretty red mushroom, a coral. I know a substantial number of mushrooms, but the ones I care about, depending on the season, are chanterelles, Porcini, Matsutaki, black trumpets, oysters and candy caps. For all others, the answer is usually, "just another mushroom…"

There is one exception. Around this time of year fluorescent glowing dots start appearing around firs and redwoods. Because they are not edible, I always forget their names.

"It's something like a Clytosibe," I might say. "But I'm not sure…"

Finally everybody decides it's simply called a Tania mushroom.

Last week I had a particularly unsatisfying day behind the house. Upon my return however, I realized I had missed something wonderful. A large number of Tania mushrooms—yellow hygrocybes—grew in the small meadow in front of the redwood grove.

I rolled around on the wet earth capturing this amazing gift, and share it with you.

I confess it has taken me a while to do so, because the image doesn't seem particularly realistic. These mushrooms truly are otherworldly. But on Saturday Barbara and Mary Anne and I walked through the woods and darted from dot to dot, unceasingly exclaiming about the bright red and yellow glow. This is what a 2 inch mushroom looks like if you roll around in front of my redwood grove and catch a tip of the sun through the branches. If you are fortunate, as I was, the resident white kite might be shrieking and soaring overhead.

A Toast for Alice

"I'm sorry, but I will have to send you a girl."

My boss was on the phone with an important client. As I heard these words, I was outraged enough to leap down his throat. Jock Hill was a tough, wiry Scotsman. But I was ready to take him on.

"Well, yes, my good man . . . " he continued. "Yes, we do have some excellent Men here. And I certainly can send you a Man. But I believe you need an Expert to solve your problems."

It was 1973, we were in a small town outside of Geneva, at the European support center for the world's leading super computer company. The compiler at the Technische Hochschule Vienna was down hard and they were desperate. I had been on the development team in Silicon Valley and knew the product intimately. They had to suck it up and listen to a 23-year-old American girl possessing a mere bachelor's degree.

Incredibly, this group of mathematics professors—Herr Doktoren Diesen and Herr Professoren Daten—eventually bonded with me to the extent that I was to be their guest at the Royal Opera Ball that honored the school—a highlight of my life. But it's the often repeated apology for my gender that flashed back into my mind, resurrected by yet one more story of how few women hold technical management positions in Silicon Valley today.

Jock Hill was not a bad guy, and I might have been well served to translate my rage into his disarming style sooner than I did. But it was rage that propelled me through those early years, a rage that I fortunately was able to channel into success.

Yesterday was Alice's birthday. I thought I should pass on some grandmotherly wisdom. In a conversation with Beth recently I jotted down the words "strength without aggressiveness." It's such an appealing concept. It definitely sounds like wisdom.

But I look around the world—at the presidential campaign and Donald Trump; at ISIS terror raging across the globe; at the ongoing challenges of being a woman in a "man's" field.

"A rage for life." That's the toast I offer you, my sweetheart. I know you have it, I've seen it in your eyes. Never lose it.

"A rage for life!"

A Good Friday

I snuck into London for just over 24 hours on Good Friday—perhaps the only sunny day of the year so far.

At the beginning of a long day of walking I passed a greengrocer on Edgewater Road and couldn't resist the giant, dark red cherries. The storekeeper offered to wash them for me after apologizing for the price—£12 a kilo.

A few delicious cherries later I knew he was from Kurdistan, had endlessly deep eyes, and a lot of thoughts on American politics.

"Something important happened in America eight years ago, and now it's time for a woman president. She will win, and do a good job."

I still can come up with no commentary on this amazing interaction, just a desire to pass it on.

I walked for miles along the Thames Trail through London and remembered two weeks spent walking from Oxford to London with my friends Linda and Sharon in February 2012. That walk healed a lot of my pain and launched me into this love of writing.

I crossed many bridges, walked in the sun, watched skateboarders, jostled with the crowds, and blessed my good fortune in life.